Direct current

| This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Direct current (DC) is the unidirectional flow of electric charge. Direct current is produced by sources such as batteries, power supplies, thermocouples, solar cells, or dynamos. Direct current may flow in a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or even through a vacuum as in electron or ion beams. The electric current flows in a constant direction, distinguishing it from alternating current (AC). A term formerly used for this type of current was galvanic current.[1]

The abbreviations AC and DC are often used to mean simply alternating and direct, as when they modify current or voltage.[2][3]

Direct current may be obtained from an alternating current supply by use of a rectifier, which contains electronic elements (usually) or electromechanical elements (historically) that allow current to flow only in one direction. Direct current may be converted into alternating current with an inverter or a motor-generator set.

Direct current is used to charge batteries and as power supply for electronic systems. Very large quantities of direct-current power are used in production of aluminum and other electrochemical processes. It is also used for some railways, especially in urban areas. High-voltage direct current is used to transmit large amounts of power from remote generation sites or to interconnect alternating current power grids.

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

|

|

Contents

History[edit]

The first commercial electric power transmission (developed by Thomas Edison in the late nineteenth century) used direct current. Because of the significant advantages of alternating current over direct current in transforming and transmission, electric power distribution is nearly all alternating current today. In the mid-1950s, high-voltage direct current transmission was developed, and is now an option instead of long-distance high voltage alternating current systems. For long distance underseas cables (e.g. between countries, such as NorNed), this DC option is the only technically feasible option. For applications requiring direct current, such as third rail power systems, alternating current is distributed to a substation, which utilizes a rectifier to convert the power to direct current. See War of Currents.

Various definitions[edit]

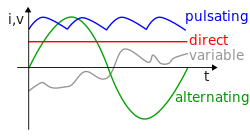

The term DC is used to refer to power systems that use only one polarity of voltage or current, and to refer to the constant, zero-frequency, or slowly varying local mean value of a voltage or current.[4] For example, the voltage across a DC voltage source is constant as is the current through a DC current source. The DC solution of an electric circuit is the solution where all voltages and currents are constant. It can be shown that any stationary voltage or current waveform can be decomposed into a sum of a DC component and a zero-mean time-varying component; the DC component is defined to be the expected value, or the average value of the voltage or current over all time.

Although DC stands for "direct current", DC often refers to "constant polarity". Under this definition, DC voltages can vary in time, as seen in the raw output of a rectifier or the fluctuating voice signal on a telephone line.

Some forms of DC (such as that produced by a voltage regulator) have almost no variations in voltage, but may still have variations in output power and current.

Circuits[edit]

A direct current circuit is an electrical circuit that consists of any combination of constant voltage sources, constant current sources, and resistors. In this case, the circuit voltages and currents are independent of time. A particular circuit voltage or current does not depend on the past value of any circuit voltage or current. This implies that the system of equations that represent a DC circuit do not involve integrals or derivatives with respect to time.

If a capacitor or inductor is added to a DC circuit, the resulting circuit is not, strictly speaking, a DC circuit. However, most such circuits have a DC solution. This solution gives the circuit voltages and currents when the circuit is in DC steady state. Such a circuit is represented by a system of differential equations. The solution to these equations usually contain a time varying or transient part as well as constant or steady state part. It is this steady state part that is the DC solution. There are some circuits that do not have a DC solution. Two simple examples are a constant current source connected to a capacitor and a constant voltage source connected to an inductor.

In electronics, it is common to refer to a circuit that is powered by a DC voltage source such as a battery or the output of a DC power supply as a DC circuit even though what is meant is that the circuit is DC powered.

Applications[edit]

| This section requires expansion with: more examples and additional citations (see also introduction). (October 2015) |

Domestic[edit]

DC is commonly found in many extra-low voltage applications and some low-voltage applications, especially where these are powered by batteries or solar power systems (since both can produce only DC).

Most electronic circuits require a DC power supply.

Domestic DC installations usually have different types of sockets, connectors, switches, and fixtures from those suitable for alternating current. This is mostly due to the lower voltages used, resulting in higher currents to produce the same amount of power.

It is usually important with a DC appliance to observe polarity, unless the device has a diode bridge to correct for this.

Automotive[edit]

Most automotive applications use DC. The alternator is an AC device which uses a rectifier to produce DC. Usually 12 V DC are used, but a few have a 6 V (e.g. classic VW Beetle) or a 42 V electrical system.

Telecommunication[edit]

Through the use of a DC-DC converter, higher DC voltages such as 48 V to 72 V DC can be stepped down to 36 V, 24 V, 18 V, 12 V, or 5 V to supply different loads. In a telecommunications system operating at 48 V DC, it is generally more efficient to step voltage down to 12 V to 24 V DC with a DC-DC converter and power equipment loads directly at their native DC input voltages, versus operating a 48 V DC to 120 V AC inverter to provide power to equipment.

Many telephones connect to a twisted pair of wires, and use a bias tee to internally separate the AC component of the voltage between the two wires (the audio signal) from the DC component of the voltage between the two wires (used to power the phone).

Telephone exchange communication equipment, such as DSLAMs, uses standard −48 V DC power supply. The negative polarity is achieved by grounding the positive terminal of power supply system and the battery bank. This is done to prevent electrolysis depositions.

High-voltage power transmission[edit]

High-voltage direct current (HVDC) electric power transmission systems use DC for the bulk transmission of electrical power, in contrast with the more common alternating current systems. For long-distance transmission, HVDC systems may be less expensive and suffer lower electrical losses.

Other[edit]

Applications using fuel cells (mixing hydrogen and oxygen together with a catalyst to produce electricity and water as byproducts) also produce only DC.

Light aircraft electrical systems are typically 12 V or 28 V DC.

Trivia[edit]

The Unicode code point for the direct current symbol, found in the Miscellaneous Technical block, is U+2393 (⎓).

See also[edit]

- Electric current

- High-voltage direct current power transmission.

- Alternating current

- DC offset

- Neutral direct-current telegraph system

References[edit]

- ^ Andrew J. Robinson, Lynn Snyder-Mackler (2007). Clinical Electrophysiology: Electrotherapy and Electrophysiologic Testing (3rd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7817-4484-3.

- ^ N. N. Bhargava and D. C. Kulshrishtha (1984). Basic Electronics & Linear Circuits. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-07-451965-3.

- ^ National Electric Light Association (1915). Electrical meterman's handbook. Trow Press. p. 81.

- ^ Roger S. Amos, Geoffrey William Arnold Dummer (1999). Newnes Dictionary of Electronic (4th ed.). Newnes. p. 83. ISBN 0-7506-4331-5.

External links[edit]

- "AC/DC: What's the Difference?".

- "DC And AC Supplies" (PDF). ITACA. External link in

|publisher=(help)

|